What Is The Rotator Cuff?

The shoulder is a ball and socket joint. The ball (the head of the humerus) is relatively large compared with the socket (the glenoid – part of the shoulder blade). This arrangement provides for a large range of motion compared to other more constrained ball and socket joints – such as the hip.

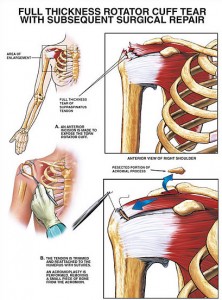

Four tendons attach to the humeral head, acting to rotate the shoulder, and hence the arm, and keep it secured in its socket. This group of four tendons are collectively called the rotator cuff as they form a “cuff” around the joint. The supraspinatus tendon is the most commonly injured. It attaches to the top of the head and acts to initiate raising of the arm. The subscapularis tendon sits at the front and it acts to internally rotate the arm (the movement performed when arm wrestling). There are two tendons at the back of the humeral head (Infraspinatus and Teres Minor) which externally rotate the arm (such as when reaching out to the side)

What Is A Rotator Cuff Tear?

This is a tear in one or more of the above tendons. Rotator cuff tears can be the result of an injury such as a fall on an outstretched hand. Most occur slowly over time (degenerative tears). People often present with pain on shoulder movement, particularly lifting or overhead activities.

Rotator cuff tears are common – about half of people over the age of 70 will have a rotator cuff tear on an MRI scan. However, the majority of these cause no problem and do not require treatment. Unfortunately, rotator cuff tears do not heal by themselves if left alone.

If a tear is causing pain and limiting movement, then it is worth investigating further.

How to Diagnose a Rotator Cuff Tear

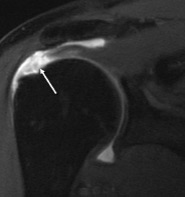

Examining a patient’s shoulder will indicate the likelihood of a tear. This can then be confirmed with an MRI scan. An MRI scan will identify the size and type of tear and help to determine if surgery is worthwhile.

Examining a patient’s shoulder will indicate the likelihood of a tear. This can then be confirmed with an MRI scan. An MRI scan will identify the size and type of tear and help to determine if surgery is worthwhile.

Other pathology is frequently associated with a rotator cuff tear. These will be identified by examination and the MRI scan and include long head of biceps inflammation, AC (acromio-claviclular) joint degeneration and shoulder impingement.

Treatment for a Rotator Cuff Tear

Many small tears which are minimally affecting shoulder function can be expected to do well with a trial of non-operative management. This involves a combination of anti-inflammatory medications, corticosteroid injection to reduce inflammation and physiotherapy to restore strength and movement.

If non operative management is unsuccessful or the tear is large or acute then surgery should be considered.

Rotator Cuff Repair

Surgery involves stitching the torn tendon back onto bone. Traditionally this was done through a large open incision on the side of the shoulder. Arthroscopic surgery involves inserting a small underwater camera into the joint to enable the repair through “keyhole” incisions. The aim is to produce the same long term outcome as open surgery but with smaller scars (and thus better appearance), less trauma to the muscles and less risk of infection.

The risk of infection is less than 1%. There is a risk of stiffness after surgery (more common in diabetics) of around 10% but this usually spontaneously resolves with time. Not all tears go on to heal with surgery. Surgery works best for smaller tears, younger patients (<70 years) and non-smokers.

Recovery after surgery is longer than most patients would prefer. It takes three months for the tendon to reliably heal onto the bone. Patients are in a sling for 6 weeks following surgery and cannot drive during this time. People continue improving for up to 18 months post-surgery.